Gamifying the Workplace

Caitlin Petre

Anyone who has read The Adventures of Tom Sawyer no doubt remembers the fence-painting scene. Consigned as a punishment by his Aunt Polly to spend a Saturday whitewashing 30 yards of wooden fence, Tom instead recruits neighborhood boys to do the chore for him. He convinces his marks that fence painting—far from being drudgery—is an inherently pleasurable activity. Tom spends the day relaxing in the shade as the boys pay him in marbles, apples, and other childhood treasures for the privilege of taking a turn with the paintbrush.

According to Rajat Paharia, founder and chief product officer of the business gamification company Bunchball, the fence-painting scene teaches a timeless and simple lesson: the difference between work and play is “completely in our heads.” With the right tactics, writes Paharia in his book Loyalty 3.0, “anything that is considered work can be turned into play—something that people want to do.”

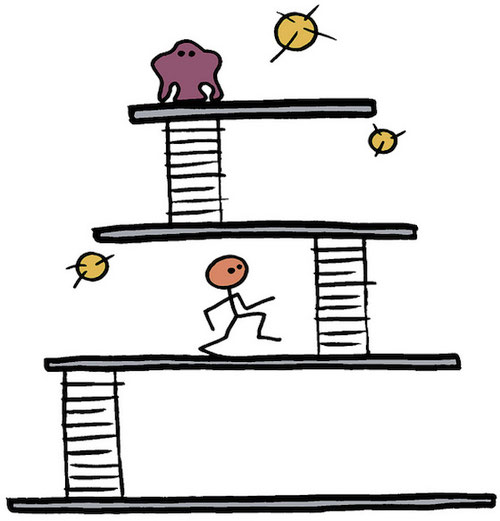

This is the founding premise—and the promise—of the workplace gamification movement. Gamification aims to boost employees’ motivation and productivity by incorporating videogame features into work. In a gamified office, a salesperson might try to outrank her colleagues on a digital leaderboard by logging the most cold calls; a customer service representative could earn a badge for resolving a certain number of complaints.

So far, gamification has been most popular for managing distributed office workers whose jobs are both interactive and relatively easy to quantify. But a burgeoning number of well-funded tech startups, including Paharia’s Bunchball, are betting that the practice will spread. Their software has been accompanied by a bevy of articles and books, written by executives, consultants, and academics, which tout the potential of gamification to increase both employee satisfaction and companies’ bottom lines.

Where did the business world’s seemingly sudden fixation on gamification come from? What does it portend for the social and material relations of the American workplace?

True to Silicon Valley form, gamification evangelists tend to treat playing at work as an entirely novel phenomenon. “Gamification done right points toward a radical transformation in the conduct of business,” write professors Kevin Werbach and Dan Hunter in the opening pages of For the Win: How Game Thinking Can Revolutionize Your Business. Paharia’s Loyalty 3.0 promises to “revolutionize customer and employee engagement with big data and gamification.” Nowadays, pro forma annual performance reviews don’t cut it, these authors say. Reared on a steady diet of videogames and social media, the rising cohort of millennial workers expects continuous performance feedback—and digital technologies can deliver it.

But workplace play is not actually a radical break from the past. Workers have long used games to cope with what ethnographer Donald Roy called the “beast of monotony.” In the manufacturing plant where Roy embedded in the 1950s, machine workers passed the time with playful rituals and pranks. One worker would switch the settings on another’s machine when he went to the bathroom; another stole a coworker’s banana from his lunchbox every day.

When Michael Burawoy conducted research in the same plant three decades later, he discovered that games had become even more integrated into daily work. Burawoy and his fellow machine operators combatted boredom by competing to “make out”—their term for producing in excess of the quota set by management. Workers who made out were eligible for a small bonus, but, according to Burawoy, this wasn’t what motivated them. Instead, they played for “prestige, sense of accomplishment, and pride.”

Though workers found the shop floor game fun and satisfying, Burawoy argues that it hurt them in the long run. Rather than organizing to extract better pay or working conditions from management, workers focused on competing against each other. The games, he writes, enlisted them “in the intensification of [their] own exploitation.”

If, as Burawoy argues, workers’ games ultimately served the interests of management, perhaps it was only a matter of time before managers began implementing games proactively rather than waiting for workers to initiate them. Digital technologies have aided this effort by enabling an unprecedented level of competition and surveillance. Managers and workers alike can access any “player’s” performance stats in real time. Digital leaderboards reveal which workers are the top performers and which, in the euphemistic parlance of the gamification literature, need a bit of “extra encouragement.”

Gamification’s blend of quantification, competition, and surveillance has led some thinkers to characterize it as a digital-era version of Frederick Winslow Taylor’s “scientific management.” At the turn of the 20th century, Taylor, a mechanical engineer, famously monitored shop floor workers with a stopwatch in order to make their labor more systematic and efficient. The sophisticated digital leaderboards available to managers today make Taylor’s stopwatch seem quaint by comparison—leading one group of interactive media scholars to christen gamification “Taylorism 2.0.”

To conceive of gamification simply as Taylorism on steroids is to miss something important, however. Scientific management isn’t much concerned with workers’ happiness on the job: Taylor focused more on how quickly a worker could carry an ingot of pig iron than how he felt doing it. Henry Ford, who implemented many tenets of Taylorist management on his automobile assembly lines, wrote in his memoir that “the [worker’s] sole object ought to be to get the work done and get paid for it.”

By putting worker satisfaction front and center, the gamification literature explicitly repudiates this kind of thinking. With a striking degree of consistency, prominent books on gamification depart from a single premise: there is an “engagement crisis” in the contemporary American workplace. “According to Gallup surveys,” writes Paharia, “70 percent of people who go to work every day aren’t engaged in their jobs.” Werbach and Hunter cite the same Gallup data, as does Brian Burke, a vice president at the technology research firm Gartner, Inc., in Gamify: How Gamification Motivates People to Do Extraordinary Things. To the gamifiers, it’s not enough that workers be proficient and effective in their jobs—they must be emotionally invested in them as well.

This fixation on worker engagement comes not from Taylorism, but from an alternative management theory called the human relations school. Founded in the 1930s by a Harvard Business School professor named Elton Mayo, the human relations school positioned itself as a corrective to the hyper-rationalist tendencies of Taylorism. Where Taylor believed in timing workers on the job, Mayo advocated talking to them. Borrowing from psychoanalytic methods, he argued that listening non-judgmentally to workers’ grievances was the best way to boost their satisfaction and compliance.

Mayo’s focus on the social and emotional dynamics of the workplace turned out to be perfectly suited for the transition in the United States from a manufacturing-based economy to a service-based one. When interacting with customers, writes sociologist Arlie Hochschild, “the emotional style of offering the service is part of the service itself, in a way that loving or hating wallpaper is not a part of producing wallpaper.” The emotional demands of service sector jobs have produced what organization theorist Peter Fleming calls an “authenticity fetish” in management discourse, in which employees are instructed to “just be themselves” at work—within carefully circumscribed limits, of course.

What most clearly sets apart these emotionally inflected managerial approaches from Taylorism is their rejection of the idea that workers are, first and foremost, rational economic actors. The gamification movement adopts a similar premise. Loyalty 3.0, For the Win, and Gamify all make the case that companies’ reliance on instrumental rewards—e.g., money, promotions, punishments—to shape workers’ behavior reflects an incomplete and superficial understanding of what truly motivates action. Managers must think of workers as “autonomous agents striving for fulfillment,” write Werbach and Hunter, “not as black boxes or simplistic rational profit maximizers.”

Gamification promises to do just that by tapping into a richer and more complex conception of human nature. Workplace games are designed to trigger workers’ “intrinsic” motivations, such as the desire for mastery, autonomy, progress, and social interaction. These motivations are, in Paharia’s words, “innate, not learned, and … proven to be universal.” Or, as Werbach and Hunter put it, “A well-designed game is a guided missile to the motivational heart of the human psyche.” If rationalized capitalism’s excessive focus on money produced the so-called engagement crisis, gamification’s focus on meaning is what we’re told will solve it.

But there is a striking inconsistency here. While workers have rich, complex, and varied motives for playing workplace games, managers’ motives for implementing such games are depicted as strictly extrinsic and instrumental: to boost performance and profit. The stark juxtaposition between workers’ and managers’ motives sometimes produces unintentionally humorous passages. According to Werbach and Hunter, “fun is an emergent, contingent property that can be fiendishly hard to pin down. The best way to tell if your system is fun is to build it and test it and refine it through a rigorous design process.” For managers under unrelenting pressure to eke out higher productivity, it’s understood that gamification will not be much fun at all; the line between work and play remains clear and firmly drawn.

Perhaps the best way to understand gamification, then, is as a Taylorist wolf in Mayo’s clothing. As advances in digital technology allow for both sophisticated quantitative tracking and deeply absorbing user experiences, gamification marries rational and emotional management strategies in potent new ways.

A crucial question follows: is gamification powerful enough to produce meaningful change in the social relations of workplaces where it is implemented? Proponents and detractors alike often answer this question with a resounding yes. Paharia promises managers that gamification gets “the people who work for you to help make your business—which is really their business—more successful.” The authors of Taylorism 2.0 highlight a similar theme, though with a much darker sheen: “The game provides the system for disciplining the worker, and the worker subjects herself to the system for a reward structure that is fun and recognizable.” While the normative implications of gamification are hotly debated, there is an emerging consensus that managerially imposed games will create the perception of alignment between employee and organizational objectives.

But it’s also possible to envision other outcomes. As gamification platforms spread and lose their novelty, workers may come to find them more condescending and irritating than engaging. At the call center Fleming studied, employees resented the company’s attempts to make the job “fun” through parties, casual dress codes, and brightly colored offices. Similarly, workers given a choice may opt out of playing games, while those whose participation is mandatory may play halfheartedly, eventually leading management to abandon gamification efforts.

Alternatively, employees may cultivate a sense of solidarity despite—or even because of—their immersion in highly gamified working environments. Digital newsrooms provide a surprising and instructive case study here. With the advent of online audience metrics that track the popularity of digital content in clicks, likes, and shares, editorial work at many news websites is becoming increasingly gamified. At Gawker Media, where I conducted ethnographic research, individual writers’ “traffic stats” were displayed on large digital leaderboards that adorned the walls of the office.

Many Gawker Media writers and editors described feeling addicted to the continuous, real-time feedback that analytics platforms provided. Some reported obsessively checking their stats even when they were socializing with friends or otherwise off-duty. Editorial staffers were, in other words, highly engaged “players” of the traffic game. It would hardly be surprising if, like Burawoy and his fellow shop floor workers, they were more focused on beating each other’s metrics than organizing collectively to secure better pay and working conditions.

However, things played out a bit differently at Gawker. Addictive and competition-inducing as the traffic leaderboards may have been, they were also crystal-clear visual representations of each writer’s value to the company. Several writers strategically leveraged the data in exactly this way, invoking their stats when negotiating for raises and promotions. And in May 2015, Gawker’s editorial employees voted overwhelmingly to form a union with the Writers Guild of America East. Nearly a year later they ratified a contract—the first of its kind at a digital media organization. Editorial staff at several other similarly metrics-focused online media companies—including Vox, Salon, the Huffington Post, and Vice—have since followed suit.

True, digital journalists are a relatively privileged and highly educated group; they are probably not broadly representative of workers in gamified work environments. But it is telling that the writers’ intense desire to beat their colleagues and achieve ever-higher personal bests did not diminish their drive to seek fair material compensation for their work. Thanks to gamification, the line between work and play may be blurring. But the line between workers and management doesn’t have to.